- Home

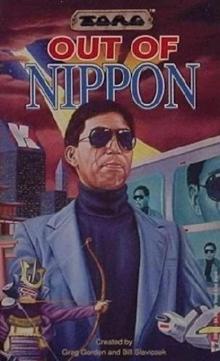

- Out Of Nippon

Nigel Findley

Nigel Findley Read online

Torg

The Possibility Wars

The Near Now … Later today, early tomorrow, sometime next week, the world began to end.

They came from other realities, raiders joined together to steal the awesome energy of Earth’s possibilities. They have brought with them their own realities, creating areas where rules of nature are radically different — turning huge portions of the Earth into someplace else.

At first it seemed that Japan, the Land of the Rising Sun, was unaffected. The borders of the island nation were surrounded by dark clouds and stormy weather, but, otherwise, the country seemed the same.

But it soon became apparent to those who could see that something was wrong in Nippon. Powerful megacorporations grew into existence almost overnight, and they absorbed much of corporate Japan. New technological breakthroughs happened frequently, but the spiritual side of Japan, its heart and soul, was shrinking.

But standing between Japan, and Earth, and total victory for the evil High Lords’” are the Storm Knights’”, men and women who have weathered the raging storms of change and continue to fight off the invaders.

The Possibility Wars™

created by Greg Gorden and Bill Slavicsek

Out of Nippon

by Nigel Findley

Chapter One

Night in downtown Tokyo was a surrealistic vision, Nikki Carlson thought for the thousandth time. The tall corporate headquarters buildings that surrounded her were ziggurats of light reaching into the sky, impressionistic sculptures created by artists who used glowing gems as their medium. Anti-collision lights on V/STOL jump-jets threaded their ways between the buildings, or drifted above them, like harsh and brilliant stars that had taken to wandering free of the firmament. And below, the wide streets of the Marunouchi district were rivers of light, even this late at night; Tokyo seemed to be a city that never really slept.

In crystal-clear air, the view would have been magical enough. But the night wasn’t clear. Tokyo, and the whole of Japan, or so she’d heard, was covered by a thin mist that never really cleared. Meteorologists on NHK, the national broadcasting system, described the mist as a “minor climatic aberration,” no doubt caused by the upheavals that were occurring elsewhere in the world. Nikki wasn’t sure that she quite believed that.

She thought that the mists had first cloaked Tokyo before the face of the world had started to change, but she wasn’t certain.

She shrugged. It didn’t really matter. The mist was here, and it made the night more than magical. The closer or brighter lights flared into rainbow-hued ha-los, while those in the middle distance were softened and diffused. What was even more beautiful, Nikki thought, was the way the mist seemed to pick up the lights of the city until the air itself glowed, shading to a shimmering mother-of-pearl hue directly above. It was like being in a water-color painted by a master.

Nikki rested her forehead against the cool glass of the window and looked down. From here, on the tenth floor, the mist made it difficult to make out individual cars as they cruised down Etai-dori, the street on which this building was situated. Further down Etai-dori was the glass monolith that was the Kanawa Corporation building, two hundred and fifty meters high, sixty-plus stories, the great steel K mounted on its sharply-sloping roof facing the open sky. The Kanawa edifice dwarfed the buildings around it, just the way that Kanawa Corporation dwarfed the corporations those buildings represented.

In a country that sometimes seemed to be run by the large corporations, Kanawa was the premier megacorporation. Nikki remembered seeing a program on NHK that itemized some of the major organizations directly owned by Kanawa. In some ways, the size of the list, and what it implied about the pervasiveness of Kanawa’s influence, was frightening. Back in the States, people had often joked about corporations like General Foods indirectly owning everything that was worth owning… or, at least, they had joked about that before the upheavals, what the Japanese oh-so-politely called Kawaru, “the Change.” Here in Japan the jokes about global ownership weren’t funny.

One of the few companies that Kanawa didn’t own seemed to be the one that Nikki worked for, Nagara Corporation. An incredibly successful research company, Nagara apparently had sufficient financial clout, and sufficient investor confidence on the Nikkei Stock Market, to fight off not one but two hostile takeover attempts by an outfit that was generally suspected to be a front for Kanawa. The independence of Nagara, particularly when threatened by an opponent the size of Kanawa, gave Nikki a strong sense of pride.

Which was amusing, she had to admit. Nagara was in no way “her” company, and she had little enough reason to feel any loyalty toward it. She was far removed from the rarified heights of the corporate pyramid where such matters were conducted, almost as far as the cooks and others who usually worked in the cafeteria where she now stood. Further, she wasn’t even fully accepted by the people with whom she worked on a daily basis. After all, she thought wryly, how could I be? Nikki Carlson was an American and a woman, two strikes against her in xenophobic and chauvinistic Japan.

Despite that, though, she did enjoy working for Nagara. When she’d arrived in Japan, newly graduated from Berkeley with a degree in genetics, her intention had been to find work that would support her at a basic level for five or six months while she learned something about the country. After half a year or so of working, she’d planned to spend whatever money she’d saved to travel around Japan, and maybe elsewhere in Asia. Then she’d intended to return to America and decide whether to enroll in graduate school or try her luck in the work force with only a Bachelor of Science degree.

But things never work out the way you think they will, do they? Nikki mused. She’d hoped to get a job teaching English, a thriving business in Tokyo. Or maybe she’d be lucky enough to track down some modelling jobs. (After all, she was tall and blonde, with bright blue eyes, which made her very “marketable” in the modelling industry. Despite the anti-Western bias shown by Japanese culture, there was a great demand for people with a “stereotypical” Western appearance in the print and TV advertizing industry.) Nikki hadn’t come to Japan seeking a career, so a big income wasn’t an issue. All she wanted was enough to live on, with hopefully some savings left over for travel.

It was sheer luck, “Fate,” her mother would have called it, that Nikki was practicing her Japanese by reading the Tokyo Shimbun newspaper as she ate a frugal dinner in a little back-alley yakitori bar. The ad was in the “Careers” section, which Nikki didn’t usually bother to read, and she’d certainly have skimmed over it if it hadn’t been written in both Japanese and English.

A research company called Nagara Corporation was looking for lab technicians, the ad had stated. Requirements included a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry, genetics, or a related discipline, and hands-on experience with automated genetic analysis equipment. Nikki read the ad with amazement: it could almost have been written specifically for her. Her personal experience with genetic analyzers wasn’t extensive. But the latest generation of the computerized machines had just come onto the market, the lab in which she’d worked at Berkeley had been the “beta test” site for one such product, so there wouldn’t be many people with more experience, or so she figured.

Nikki had thought through her options as she’d finished off her glass of Sapporo beer. As she’d found out over the past week, the demand for English teachers wasn’t anywhere near as great as she’d expected. And, while there was a demand for models, she’d come to realize it would take time to make the contacts she’d need to break into that industry. Money was becoming an issue, which meant that she couldn’t afford that time. She had to find a job soon. She could probably have found work as a cocktail waitress, she’d figured, making barely enough money to live on an

d spending much of her time avoiding the wandering hands of drunk Japanese sararimen ... But here was something in her own specialty; this was the kind of job she’d been thinking of applying for when she eventually returned to the States. She’d be crazy if she didn’t apply for it, no matter how unlikely it was that she’d get it.

She’d checked the address on the ad. The normal procedure would have been to send in her resume and wait for them to contact her. But what the hell? Her trip to Japan was supposed to be a learning experience, wasn’t it? And applying for a job in person, without even a letter or a phone call first, something she’d never have had the courage to do at home, was certainly that…

The address had turned out to be the Nagara Building, a forty-story block in the Marunouchi district, only a couple of blocks from the Marunouchi Central Station. Although definitely a large building in its own right, the bronze-glass tower had seemed to fade almost into insignificance in comparison to the Kanawa monolith two blocks away, half as tall again as the structure in front of which Nikki had stood. The Nagara logo, a representation of an origami crane, surrounded by a circle of stars, had been inlaid into the marble lobby floor in what looked like gold, she recalled.

Afterward, Nikki found herself unable to remember any real details of the interview process. There were vague recollections of a series of managers, all male, all Japanese, asking her questions about her background, her experience, her goals, even her hobbies and interests. And then she remembered being led through gleamingly clean labs, where white-coated technicians were working with computerized analysis equipment that made the “cutting edge” gear she’d used at Berkeley look like it belonged in a museum. Finally, she remembered meeting a hard-faced man in his late thirties, whose name she hadn’t caught at the time, who offered her a firm handshake and brusquely welcomed her to the Genetic Research Division of Nagara Corporation. It was only later that she’d learned the man was Agatamori Eichiro, Eichiro-san, the senior manager in charge of the division for which she now worked.

Nikki moved back from the window with a smile. Nagara was a pretty damn good place to work, it had turned out. There was no doubt that the company did much more than the vast majority of American companies to take care of their employees. Housing, security, sometimes even cradle-to-grave medical coverage …

And amenities like this cafeteria, she added mentally, looking around her. She well knew that the price of food in Japan had been rising steeply over the last couple of years, in large part due to the takeover of agricultural land by the corporations. The cost of rice had almost doubled in the three years since Nikki had arrived in Japan, and when you looked at what it cost to buy a good steak … No wonder the burakumin, the poor and homeless, like the ones who managed (somehow) to subsist in the middle of the city, were finding it ever harder to eke out an existence.

The cost of food wasn’t much of an issue for those lucky enough to work for Nagara and other corporations like it, though. The sararimen, and sarari women, she carefully appended, employed by Nagara could eat at this cafeteria and others like it, and buy much of the food they needed for their families from stores at special “corporate rates.” The price of food, here and in the “approved” stores, was kept artificially low for Nagara employees. Ridiculously low: Nikki could buy a steak sandwich in the cafeteria for 680¥, or a little under five dollars at the current rate of exchange, while in the restaurants of Marunouchi it would have cost her almost five times that sum. Japanese-style food, yakitori, perhaps, or ben to box lunches, cost even less. (Predictable, Nikki thought. Western visitors to Japan quickly found that they paid a very solid premium for trying to emulate the lifestyle they had at home.) Understandably, Nikki cooked many of her meals with food purchased under the “corporate plan” and ate most of the rest at the cafeteria. She was so much of a regular, and always made a point to be polite to the serving staff, that she thought she’d started to see a thawing in their icy impassiveness.

Even the location of the cafeteria reflected the attention the corporation paid to its employees. In just about any American facility, the employee cafeteria would have been in the basement, or maybe in a lowly outbuilding, while the higher floors of the office block would be reserved for important things like managers’ offices. Here? The cafeteria was in one corner of the tenth floor, with two entire walls made up of windows, and high enough to provide an excellent view. It was an interesting choice, and a good one, Nikki thought. The cafeteria gave all the shaikujin, the devoted employees, a wonderful view of the heart of Tokyo, and the sense that they were part of something very great and very important. It told them that they held a significant place in the cosmos that was Japan.

The cafeteria was closed now, of course. Like most of the corporate skyscrapers around it, the Nagara headquarters worked on a semi-official day of seven in the morning to five or six in the evening. Enough employees worked late frequently enough to warrant running dinner service until nine at night. After that, all but the most dedicated sararimen were on their way home, or maybe boozing it up at the Tengu, a chain of restaurants and bars that had a franchise location only two hundred meters from the Nagara building. By twelve-thirty, Nikki checked her watch; Twelve-forty- five, she corrected herself — the place was always deserted.

Almost deserted. That was the one thing she could take “issue” with about her work. She simply loved her job. (How often had she heard that statement, spoken in a sarcastic tone? But in her case it was true.) She’d quickly realized she had a knack for using the sometimes-temperamental automated analyzers; she often thought it was almost as if they “understood” each other, she and the machines. Because of the two strikes already against her — female and gaijin (foreigner) — it had taken her supervisors some time to recognize this. But when they did — thanks, in fact, to Nikki pulling her direct boss’s fat out of a really big fire of his own creation — she had to admit that they moved fast. More than a few noses were put out of joint when she was transferred to another department within the Genetic Research Division, and put in charge of a workgroup — designated Group Five — that included people who had considerably more formal training and seniority than she. In most cases, she smoothed the ruffled feathers not through any feats of diplomacy, but simply by being good, damn good, at what she did. And, she told herself, that’s one thing that everyone here recognizes and admires: competence.

So in most areas, her job was as close to perfect as she could imagine. The only sore point was the hours. It wasn’t that her bosses were slavedrivers, keeping her here until well after midnight. No, it was only the laws of physics and chemistry that were dictatorial. (And who do I appeal those to? she wondered with a grin.) There were certain chemical processes used in genetic analysis that simply took one hell of a long time. Even though they didn’t always have to be “baby-sat” from start to finish, there did have to be people around at initiation and completion … whenever completion might happen to be. And Nikki was a good enough workgroup leader to know not to ask her colleagues to do something she wouldn’t do herself. What this meant was that, all to often, Nikki found herself in her basement lab either hours before most people would be waking up, or hours after most had left for the day.

“No, no, no, how many times do I have to tell you? The breakfast line-up doesn’t start for another five hours.”

With a broad smile, Nikki turned at the amused voice behind her. “Breakfast?” she asked in mock surprise. “You mean I’m late for dinner?”

The young Japanese man who faced her shook his head in feigned disgust. “Gaijin,” he sighed. “When will you become civilized, Carrson-san ?” Nikki chuckled at the way he mispronounced her name, aping the difficulty which many of her colleagues had, or pretended to have, with the R-L combination. “I thought I’d find you here,” he added.

Nikki nodded. “I like it here, Toshikazu. It’s a good place to think.”

“Yes,” Toshikazu Kasigi agreed. (Strictly speaking, his name was Kasigi Toshikazu, in Ja

pan, the family name came first. But, as a matter of convenience, most Japanese put their given name first, in the Western fashion.) “No interruptions …” Toshikazu grinned wryly, “… most of the time.”

“The sequences are ready?” It was Nikki’s turn to sigh. “Ah, well, no rest for the wicked.”

Nikki looked Toshikazu over as she followed him out of the cafeteria toward the elevators. He wasn’t tall, he stood an inch or two shorter than Nikki’s five-foot-nine, but there was something about his slender, well-proportioned build that made her feel he was taller. He was about Nikki’s age, about twenty-four, she thought, with a smooth, unlined face that seemed to settle naturally into a wry smile, and dark eyes that flashed with humor. (Nikki remembered with scorn the Westerners who’d told her that all Japanese look alike. Idiots. Although the differences might show up in different features, Japanese faces were as distinct as American faces… to anyone who made the effort to actually look.) He moved easily, gracefully, almost, with an economy of effort that made her wonder whether he practiced any of the martial arts in his spare time.

She knew next to nothing about Toshikazu’s life outside work, she realized. She knew a lot about him, his hopes and fears, his attitudes about science, and about the social problems facing his country, that kind of thing, but, she was somewhat surprised to note, he’d never talked about his day-to-day life. Where did he live? Was he married? (She didn’t think so; no ring.) What did he do with his time? She found it intensely interesting that she knew so little, and, honestly, didn’t really worry that she knew so little, about a close friend.

Because Toshikazu was a friend, by far her closest friend in Japan, perhaps her only one, she admitted a little uncomfortably, and had become one of the brightest parts of her job. A geneticist by training, like her, he had a much better grasp of the actual biochemistry behind what they were doing, and was much more familiar than she was with the theoretical breakthroughs on which the automated analyzers were based. When she’d realized this, she’d felt acutely uncomfortable. But for his part, Toshikazu seemed to have no qualms over being in a workgroup led by someone who was his academic inferior. (When she’d eventually broached the subject with him, he’d just shrugged and said, “I’ve read the books. But all the books in the world aren’t going to give me the rapport with the machines that you have.” She’d never raised the topic again.) Apart from Nikki and Toshikazu, the other members of Group Five were in their forties and fifties — all males, technicians who’d risen as far as their talents would take them, and had been forced to face the fact that they’d never hold positions more senior than those they currently had. The age difference added the third strike against Nikki as far as they were concerned. How could they respect a female gaijin who was fifteen or more years their junior? The fact that they were the only two close in age brought Nikki and Toshikazu even closer.

Nigel Findley

Nigel Findley